May 25, 2010DOUBLE MOON: CONSTRUCTIONS & CONVERSATIONS

Review by Janis Lull

borealbooks

100 Cushman Street Suite 210

Fairbanks AK 99701-4674

ISBN 9781597091411

2009, 66 pp., $19.95

www.borealbooks.org

Double Moon reproduces pieces from several exhibitions by two Alaskan artists. My daughter and I went to see one of these shows in Fairbanks because we know the artists and their work. Margo Klass makes boxes, usually, and inside them are all kinds of found objects–nails, eggs, birch bark, sheet music. Frank Soos is a writer. The “Double Moon” of the book title suggests their collaboration. It is also the title of a construction pictured in the book and in close-up on the cover. This particular box holds an old pair of goggles with a luminous white seashell placed behind each lens. The “miniature essay” that goes with it asks, “Will we always crave more light?” This is the way Margo and Frank collaborate. She makes a construction and he responds to it in words. The combination doesn’t produce poems, exactly, and if you had stood in the door of that Alaskan gallery with us, your first thoughts would probably not have been about poetry. You might have thought you were standing in a room full of sculptures with labels next to them. But that’s not really what was in that space, and it’s not what’s in the book, either. On the page, where the photos and the text are more nearly the same size, the words seem to grow in prominence, and so does the particular selection of objects in the boxes. It’s as if the art exhibits have become a book of double poems.

Margo was a bookbinder before she made boxes, and her constructions are as carefully wrapped in cloth or paper as a finely hand-bound book. You can’t really see this perfectionism in the photos, which is a limitation. They’re beautiful photos, as beautiful as any I’ve seen of, say, Joseph Cornell’s boxes, but not as beautiful as the works are in person. Like Cornell’s, Margo’s constructions are enigmatic, although hers are more spare and less quirky than most of his. They have a classical look, even when they contain things like a pair of pliers or an old spatula. In the box, each object is transformed or re-formed into something both recognizable and new. The spatula, for example–or maybe it’s an little old baking tool for extracting small loaves from the hot oven?–stands erect on its long stem in a tall, thin box. An old ring hangs on the wall behind the spoon, maybe a pot hook or a drawer pull, just a little larger than the flattened-out scoop of the utensil. The box that holds them is open in the front and it’s covered in hand-made Japanese paper. The title is “Icon.”

![]()

Although I haven’t looked at everything in the box, by the time I get this far, I want to read Frank’s text: “What would the minimum requirements for sainthood be? A halo, of course, for effect. And the shrinkage of the body to the advantage of the soul. How little of the one and how much of the other? At least a modicum of personhood remaining? Personhood with all its attendant needs and wishes, yes, that would be the problem, wouldn’t it?”

Well, yes. I’m looking at a spatula, after all. It’s standing on its handle with its head in the air and an iron hoop for a halo, but just the same, it’s meant for handling food. It speaks of “attendant needs.” There’s more to see in this box, and in this text, but I’m satisfied with the way they go together. Whatever Margo was thinking when she housed these objects in a space the size of shoe-box, she called the assemblage “Icon,” certainly evoking saints. Frank’s response came after the construction and its title, but Margo read the response and was content to leave the two side-by-side. Whether they’re two works or one, I feel free to take the photo and the text as a pair.

I’ve been interested in Frank’s writing for a long time, especially his lyrical short stories and non-fiction (Unified Field Theory, Bamboo Fly Rod Suite). In the acknowledgments for Double Moon, he mentions me as a source of “artistic support,” although I’ve never offered (or been asked) for any critiques of his writings about the visual arts. Frank has collaborated with other artists, notably the painter Kesler Woodward. I know Kes, too, and my painting of Alaskan birches by him is the only thing I ever insure when I move. It’s irreplaceable. A box by Margo Klass would be irreplaceable in the same way, if I owned one. Kes, Margo, and Frank are all Alaskan artists, even though they don’t always make works about Alaska. Maybe only a quarter of the constructions in Double Moon is contained in the “Alaska” section. Other works were inspired by the Maine seacoast, for example, where Margo also has a studio, or by architecture, especially that of Japan, or by medieval altarpieces. Frank’s essays, a paragraph or so for each piece of art, react to rather than describe the visual work. He’s been responding this way to Margo’s art for a while now, and as he says, “As time went on, abstractions set in, wanderings in both word and image went further afield . . .“ So Margo constructs and Frank writes. You and I are left to read and interpret the conversation between them–if that’s what it is–knowing that each has chosen to let the piece and response stand together for whatever they stand for.

I’m probably not a typical reader of Double Moon. My guess is that Kes Woodward fits that description better. In his “Afterword” to the book, Kes writes that his approach is to study Margo’s sculptures first, putting off as long as possible reading Frank’s words, because the texts somehow lead him away from his “own experience.” Maybe this is what one should do. It’s what I probably would do if I were looking at a more conventional display of artwork plus explanatory labels. But I already know that’s not a good description of Double Moon, so I let myself read the words first if I want to, or I look, then read, then look again. I might just feel more at home with writing than any other art form. Kes is a painter, and he goes at these things differently.

The double art of Klass and Soos strikes most people as a variation on ekphrasis, a term from Greek rhetoric that refers to the describing or defining of one kind of art by means of another. Because I know them, I decided to interview the artists about whether they view their collaboration this way. Margo, whose works come first, does not see herself as describing or defining anything. She says she starts with composition–the arrangement of found objects in a rectangle–just a two-dimensional space at first. When she has finished assembling and arranging the objects, she begins taking some away. This adding and subtracting on a flat surface can take a long time. I saw one such “first draft” in her studio–nails and twigs laid out on a carefully ruled rectangle about the size of a piece of typing paper. When she’s finally satisfied with the flat composition, she starts thinking about building a three-dimensional box for the objects, which will naturally force her to revise her earlier ideas.

I have the impression that Frank does not look at the constructions at all until Margo considers them finished. His turn comes after hers. As in traditional ekphrasis, the writer is more likely to be seen as the definer or describer. This is how Kes Woodward evidently sees him, and why he waits until last to read the words. Do these two artists, I wondered, ever work the other way around? Does Frank ever write something and then ask Margo to create a box in response?

“Everyone asks that,” they said, but they have not done so, although they are beginning to think about the possibilities. Frank doesn’t consider himself a poet, but I would call the “mini-essays” in this book “prose poems,” and I can imagine another book (although perhaps not a gallery show) in which the words preceded the sculptures. Yet the boxes would not simply be illustrations of the writing, any more than Frank’s prose poems are descriptions or definitions of the boxes. Maybe text and photo could be displayed on facing pages.

Klass and Soos are a couple, but according to them, their artistic partnership preceded the personal one. They met when they were both in residence at the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts, and had never seen one another’s work.

“He came to my first show,” Margo said. “I was very nervous, but he looked around and then put his arm around me. That was the first time we touched.”

Later, she read some of Frank’s stories, which unlike her own work, are not classical, spare or abstract. “I was a little put off, actually,” she says now, and yet the tone of Frank’s responses to her work is very much the tone of his stories–colloquial, personal, sometimes abrupt. Here’s a typical introduction to a character from the title story of his collection, Unified Field Theory: “Bjorn Toulouse is temporarily stranded as a waitress in a truck stop off I-85 where drivers in their tractor caps read her name tag and don’t get it.” There are tricky narrators in Frank’s stories, and this device also appears in his responses to Margo’s art. Narrators known as “I” or “we” show up quite often in the “mini essays,” but it can be hard to tell if the narrator is supposed to be Frank or Margo or Frank and Margo, or somebody else entirely. The composition called “Rock Paper Scissors III,” for instance, has only a few elements: A background of old handwritten text, the kind Margo collects from second-hand stores, a pair of needle-nose pliers standing on its handles in open position, an egg-shaped object between the handles, both objects set on an old block of wood. Here’s what the text says:

Notice the size of the scissors. We’ve entered the delicate phase of the procedure. Yes, there will be cuts, but they will be made with greater precision. And the rock? Smaller, too. Made for a more accurate aim. Will it still hurt? We haven’t figured that part out yet.

About “Rock Paper Scissors III,” Margo says, “To me, it’s pure abstraction–square, circle, triangle. It’s so satisfying working with these primal elements.” An egg, a pair of pliers, a title from an old and not unpainful game. Could this piece be about a forceps delivery or anything like that? Not to the artist, or so she says. To the writer, maybe so. Readers are left to ponder this, along with the question of who “we” are who have entered “the delicate phase.” Were there two phases before “Rock Paper Scissors III”? What were the procedures? Did they hurt? Margo: I think an artist almost has to be open to just about any interpretation from the audience. I do not intend to teach anyone with my art. I simply invite people into the spaces I create.” As Frank puts it, “didacticism has become a little bit more aggressive in art since the end of abstract expressionism.” Both artists intend to buck that trend. They use words such as “evoke,” interrogate,” and “invite” in talking about their collaboration. “We are not,” Margo says, “shoving it in people’s faces.” Occasionally, however, a piece will have a personal and very specific meaning, and like Frank’s fictional waitress, Bjorn Toulouse, Margo is happy if people “get” it.

The box called “Three,” for example, encloses three stones, two light egg-shaped ones and one darker and squarer. They are held in place by two sticks that seem to join at the top, just out of sight. “What would these little souls have been bound for?” asks the text. Some viewers have seen this as a piece about three miscarriages, and that really is its origin, according to the artists. Although they do not mean their work to be didactic or limited to personal meanings, they do mean in some sense to communicate. It’s an aesthetic that T. S. Eliot would have understood.

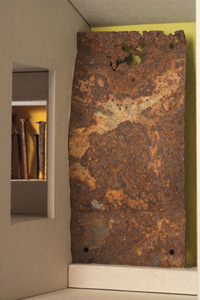

My personal favorite among the collaborations in Double Moon is “Sugimoto I,” a box inspired by the Japanese-born photographer and architect Hiroshi Sugimoto. This is one of those pieces in which some objects–in this case a handful of rusty nails and similar-sized pieces of metal–are partly hidden. The viewer has to look into a mirrored chamber– an enclosure within the enclosure–to see them. The main compartment also contains a piece of rusted metal, this time a thin sheet. The marbled rust patterns on this panel provide a lovely surface to look at, once the object is displayed to us as art, in a fancy box that could be a miniature Japanese house. And yet there are those other objects hiding there, sort of. Sharp things. This is the text:

Rust has always been the enemy of my life, always sneaking around, never taking a break, reminding me that nothing human ever lasts, reminding me that molecules have minds of their own.

Rust, I owe you everything.

The art of Margo Klass is a contemplative art. It does not shove anything in anyone’s face, certainly not a rusty nail. Frank Soos, on the other hand, is pushier. That could be why Margo didn’t like Frank’s stories at first, and why she now welcomes his collaboration. There’s nothing necessarily threatening about lovely rusted objects in a hand-made box, but when one starts to think of rust “sneaking around” defining life by its relentless decay, the tension is inescapable. Whoever is speaking in Frank’s poem says he or she or they owe “everything” to rust, to the harsh, incessant pressure of molecules that “have minds of their own.” Frank’s text affects the apparent stasis, the “pure abstraction” of Margo’s box or reliquary or whatever it is, moving it back toward the hostile reality of time, in which a former Catholic waitress named Bjorn Toulouse, “can’t face any nuns, they give me flashbacks.” The artistic spaces of Double Moon embrace both Margo’s serenity and Frank’s insistence that things tell stories. Neither would be complete without the other.