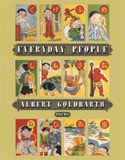

September 30, 2012EVERYDAY PEOPLE

Review by Barrett Warner

Graywolf Press

250 Third Avenue North, Suite 600

Minneapolis, MN 55401

ISBN: 978-1-55597-603-3

2012, 187 pp., $18.00

www.graywolfpress.org

The twinned weeks of Easter and Passover are a good time to read Albert Goldbarth’s Everyday People on a farm. It’s a time of mythic liberation and re-incarnation, but it’s also a time of nitrogen, cutting ground, seeding, and rolling. “The truly interesting halves/ of Hercules and Jesus are everyday people,” he writes in “Most of Us.” The grime of the everyday can be a beautiful muse and Goldbarth seduces us with its charms. This collection is a hymnal for those of us whose lives get dirty with what we do:

Worlds shake. There is gnashing, there are hosannas.

Even so, if the “condition” is “human”

it also must attend to Neil

losing at online poker tonight.

Maybe Goldbarth is a pretty good poet, but he’d have made a hell of a farmer too. His eye that sees everything and discards nothing, his thinking out loud in quiet places, the always present hum of instinct–the fight/run, fight/run bugle of his line breaks–all this would have made him very comfortable on the back of a horse. Goldbarth is also quite at home as a poet, one of the hardest working man in metric feet, sending out oversized envelopes each month, licking his stamps, and broadcasting his poems to everyone.

Goldbarth learned how to move with Norman Dubie, Marvin Bell, Lerry Levis and that whole generation of writers who mastered how to carry metaphor threads across the country and into the next century without breaking them. Each of these close cousins found his unique way to push metaphor over so much space and time. Levis did it by meandering. Dubie did it with dramatic monologues. Goldbarth does it with a storm of words, an ocean of language. He writes:

The oceans are dying. They require a hero,

or a generation of heros. The oceans are curdling

in on themselves, and on their constituent lives,

they’re rising here, and lowering there,

I swear I’ve heard them gasping.

These lines in the book’s title poem are a call to arms and awareness. Save the oceans. Save the language. The speaker’s friends are too busy “brooding over who their kids are playing with on the streets” and are “exhausted disputing how many angels can trample the truth from a twelve-dollar overcharge on a cell-phone bill.” It’s worrisome, the ocean problem, the language problem, but there’s also “the tumor and the marriage and the alcoholic uncle.”

Paranormal readers take note; the ghost of Auden haunts these lines. Consider Auden’s “Musee des Beaux Arts:”

About suffering, they were never wrong,

The Old Masters: how well they understood

Its human position; how it takes place

While someone else is eating or opening a window or just

Walking dully along.

When our lives are busy–busy with “pomp and accomplishment”–they are not our own. We need the reflected moment to carve ourselves out of the “heavy communal block.” For Goldbarth, the right to assemble is less attractive than the right to be alone, dreaming his dream of “falling through a buttonhole into the lives of everyday people.”

One such spill takes him into the heart of Darwin. “I’m sitting at Nathan’s, reading a biography of Darwin/ who, right now, is dissecting a barnacle/ no bigger than a pinhead (and with two penises.)” This was Darwin’s everyday life, as it was Einstein’s to sit on trains. We need experience and reflection in equal measure to gain the breakthroughs, and too many of us are all one and none of the other: “I tell you/ we’re amateurs, we’re sometimes bungling amateurs/ of the minutiae of our own lives.”

Goldbarth’s key moments arrive when he lets the reader in his own button holes, writing close to the everyday parts of himself. Anyone’s mind is capable of forming associations, but the heart is less inventive and this is the important middle ground we should seek in creating art:

When I heard the sounds

that gurgled from my chest as my wife was leavinginto the dense, conspiratorial Austin, Texas night

I couldn’t have said if it was defeator relief. She couldn’t have said which one

she’d have been the happiest to cause. We only knewthat I’d been wrong at times, and she’d been wrong at times,

and that our total errors, if spread out flat,become the house we live in. […] And when

enough errors accumulate there, that’s what

we call the future. Even now, as you read this,

someone in that unknowable distanceis breathing you in.

It is a shame that “The Poem of the Little House at the Corner of Misapprehension and Marvel” has to end. But in many ways it doesn’t. Anyone as prolific as Goldbarth will tend to write poems in clusters. Each poem in this collection feels like it begins in the middle of the preceding poem, as if each new poem were another branch of the former poem’s possibilities. Here are poems meant to be read as a whole group. The narrative thread and its voice change often between these eight clusters but this is a man who’ll grab at anything–a stone, a club, an insult, a joke, an idea—to hurl at the Busy Monster, to save the ocean, “–of course. What else is there to write about?”

In this way a poem whose middle confides “of lung: 300 million alveoli, that ‘if spread out flat,’/as my eighth-grade science teacher preened, ‘would come to/ 750 square feet, the entire floor space of an average house’” and ends “breathing you in” results in the next poem, “Miles,” about his mother’s lung cancer. This is much more cohesive than clever arrangements. Consider too this cluster having begun with an ocean gasping. In “Miles:”

The Anderschorns were the first of our neighbors to get

an RV, and from that day on we saw them only

at Christmastimes. “They travel around the year!”

My mother said with a kind of wonder

in her voice, as if they’d snapped the chains

of ordinary living.

The poem’s tension is anchored in the riddle of time. His mother who suffers air panic hasn’t too much left. She cannot snap the chains of her ordinary dying. The famous Anderschorns make their annual biblical appearance. He writes, “And distance is tricky—not all of it yields/ readily to our gauges and itemized lists.” Time and space, our path to understanding relativity, seem like brother and sister. “Distance is slippery./ One of its tricks: it masquerades/ as time” and “The clock: how many miles?”

The miles in the plum, in the turbot, in the caramel filling.

[…] The miles of nerve

if they were unbundled out of the boy,

is how many miles? A hummingbird is how many miles?

The long trek from the ovum to the grave.

I once said something to a woman I knew

that traveled through the death scenes in the Iliad

before it left my lips.

Not all of us like to admit that we are poets. Goldbarth takes every opportunity. How many poems begin “I was reading” or “I was writing”? Maybe one-in-two, or five-in-ten, as Goldbarth might say, given his tendency to size up rather than down. In “A Story” he clears his throat aand restarts his poem: “I call it/ the life poem: you know, first this happened and then/ this happened too. We write so little/ about the gods anymore–when was the last time Zeus/ assumed an animal form in a poem?” “A Story” navigates its way into a taco joint where the speaker, presumably waiting for his chalupa, sees a Palestinian funeral on the television which reminds him of the Sabbath service: “there was weeping enough,/ and raised-fist vows of violent reprisal enough,/to make the stones of the desert moan in pity./ I saw this. I saw this.”

In other words, you don’t just fall into a button hole. Sometimes you jump and dive into it. Once we get to know other everyday folks, to see the beauty of our shared forms–“scattered creatures into one majestic pattern”–our minds grow even more curious. Button hole jumping is just another way to say “get out of your routines” to know yourself and to see beyond the routines of others. In this, Everyday People is a book of identity and consciousness. While we can solve our own problems, like our grieving and disappointments, no single person ever has an identity that’s tall enough or a consciousness that’s broad enough to keep the oceans from dying. For that we need all of us and the help of a God or community.

I drive back home, eleven city blocks

is a million miles away.

[…] Spectroscopy: we know more now

about the composition of the stars than, say, what constitutes

an act of love in the house across the street.

Identity and consciousness shape perspective and in Everyday People we lose and find perspective many times until by the end of a poem miles are on the clock face and time is the distance you travel. A “poem” is a “story” and classic poetic form is something borrowed only for the moment. Desire and memory cross paths with war and rage and shouts so that consciousness and identity are a romance which may end in tragedy for some, marriage for others, a magical flock of geese, an airplane crash in Iowa.

Goldbarth’s “Perception Poem” is composed of three sonnets more or less stacked and each preoccupied with the seen and unseen. The first stanza takes up vision itself: “The limits of our range…[t]he stars that welt across the sky appear from Mystery and disappear in the sea in a balancing Mystery.” The second stanza is an urban legend-styled bar story describing an attractive woman who enters a bar and climbs on top. “She just stared ahead./ She didn’t make eye contact with anyone.” The woman “bared her pussy; and from out of it she fingered/ a diamond…it was a ten carat diamond,/ And none of us ever learned more than that.” In the final stanza we’re in a cave, submerged with sightless cave fish, who in spite of being blind find numerous ways to busy-up their waxy-white albino slivery lives:

Somewhere in there’s a metaphor

for us, and what we’re blind to, what enormity

we’re blind to, and how surely and emphatically we still

conduct our daily selves. The difference is: they don’t know

what they don’t know. Ours is an awful awareness,

filled with itch and wonder.

Goldbarth’s point is not whether evolution happened, but why has it stopped happening? Evolution, or change through time (or change through distance if you believe the poet), means nothing when it ceases. There must always be change. Creation tilts towards destruction when we stop imagining. “Extra! Extra!” Goldbarth is saying, snapping gum and wearing a ball cap. “Creation is our future! Read all about it!”