February 25, 2012FLIES

Review by Michael Schmeltzer

Copper Canyon Press

PO Box 271

Port Townsend, WA 98368-9931

ISBN 978-1-55659-377-2

2011, 78 pp., $16.00

www.coppercanyonpress.org

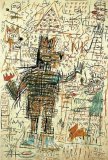

I have breaking news for the literary world: you can judge Michael Dickman’s award-winning book, Flies, by its cover.

The cover art, from an untitled piece by Jean-Michel Basquiat, has all the qualities of the poetry beneath it. Both are messy, immature, and strange (and if I’ve offended any Basquiat fans, please try to argue his success wasn’t partially based on his messy, immature, and strange vision). Both contain hints of violence and needless repetition, but are not devoid of quality; in fact, Flies is one of the rare books of poetry I couldn’t put down until I finished it. The book is surreal, engaging, and strikes a consistent tone (though if you don’t like Dickman’s particular music, the whole book will come across more drone than tone). In the end though, as sublime as moments are in this collection, as a whole it seems a bit…premature. Regardless of its flaws, however, Flies is a book worth reading, contemplating, arguing, and agreeing with.

Before I begin, let me state I am a fan of Michael Dickman’s poetic voice and the mood it sets within his work (I remember thoroughly enjoying both elements in End of the West). Whether this translates into being a fan of Dickman’s oeuvre, however, remains to be set in stone. Poetry must be more than the sum of one part, and as often as Dickman grandly succeeds in one area of a poem – a provocative image, let’s say, or stunning metaphor – he fails in another (exaggerated, compensational white space, what I can only call punchline breaks, etc.)

At his best, Dickman displays poetic techniques borrowed from Eastern tradition as well as American masters. In one poem we find him smearing feces on Issa, transforming an elegiac “world of dew” into an angst-ridden “world of shit.” In other poems we have him dipping into the pockets of Emily Dickinson and William Carlos Williams. He uses their skills to elevate his own surreal and troubled voice, sometimes to great effect. At his worst, these techniques become nothing more than gimmicks and lazy tricks, auto-tune for an inconsistent poet. In the way a clever jingle sticks in our head, Dickman gravitates toward easy, glib lines that at first strike a reader as profound or deep, but upon further inspection are nothing but gloss. For example, consider the line, “The morning makes its way up the street as a loose pack of wild dogs.” It may sound interesting (and was one of my favorite lines upon first read through), but it simply doesn’t work if you think too hard. In other words, Michael Dickman has figured out a shorthand for writing a Michael Dickman poem.

What Dickman has going for him beyond clever marketing of his biography (this is not his fault by any means, but the fault of a voyeuristic readership at large – shame on us) is a certain amount of chutzpah. Any poet who writes the somewhat corny and childlike line “light like love” or “pulled by the golden voices of children” and squeezes them by an editor has to have some nerve. Which is exactly what Flies is: a nervy book of poems haunted by family, flies, and superheroes (from a dead brother to Emily Dickinson to a “little cross,” everything flies around in this book…except maybe the flies now that I think about it).

Some lines are unabashedly sentimental (“There’s nothing better / than shaving your father’s face), others kind of silly and juvenile (“I want you to fuck my face”). Either way, the risks Dickman takes are absolutely thrilling. He is constantly risking absurdity (thank you Ferlinghetti) and the best part of this dark slapstick is whether he slips on a banana peel or leaps over it, the reader derives a certain pleasure from it; we can’t look away.

Let’s take the seemingly ridiculous opening to “Emily Dickinson to the Rescue” as an example. Not only does Dickman, in terms only my sixth-grade-self would find shocking, conjure up Dickinson taking a dump and having sex (in what order, only the speaker of Dickman’s poem will know for sure), but he also takes it a step further by planting the image of her masturbating in our heads, as if this is what the poetry world had been lacking. Dickman gives us these images rather emphatically with unimaginative line breaks.

Standing in her house today all I could think of was whether she

took a shit every morningor ever fucked anybody

or ever fucked

herself

The tactic is predictable. I get it, you dropped the f-bomb. Neither bomb detonates with any real force. For inspired use of the word fuck, read the poems “Boy in Video Arcade” by Larry Levis or “Self-Portrait with Expletives” by Kevin Clark. Clark and Levis succeed by using not so much an f-bomb, but an f-bullet. Its use is precise, layered, and does more work than two Dickman fucks, including the dull breaks. Hell, take a ride on a school bus, and you’ll probably hear a more creative use of the word. As for sexualizing Dickinson, Billy Collins undressed her years ago. It really doesn’t bring much to the table.

But I digress…Dickman starts off pretty much submerged in the toilet (where later we read his heart resides – yes, it “floats in piss”) but pulls the poem out and brings it into the heavens.

God’s poet

singing herself to sleepYou want these sorts of things for people

Bodies and

the earth

andthe earth inside

Instead of white

nightgowns and terrifying

letters

By the end of the section he magically pulls off one of the most inappropriate openings I have ever read. That alone is almost worth all the accolades the book has been given.

There is a sweetness to this passage that balances the abrasive immaturity of the opening lines. Instead of shock and ugh, we get aww shucks, a naïve tenderness perfectly pitched. Bear in mind I’m not arguing against the crass opening, nor am I some sort of prude against shitting, masturbating, or fucking. I’m arguing against half-baked writing and lazy line breaks (for instance, if one writes “invisible metal teeth,” doesn’t that imply you can, in fact, see them since you know what they are made of?)

Dickman continues the poem (a majority of the second section of this poem seems somewhat superfluous so I’m going to just bypass it) with some of the loveliest lyrics in the book.

The world is Cancer House Fires and Brain Death here in America

But I love the world

Emily Dickinson

to the rescueI used to think we were bread

gentle work and water

We’re notBut we’re still beautiful

The long line (like the undeniable fact of death) followed by the short twist (his persistent love for the world), the gorgeous three-line stanza (each line shrinking, symbolically mortal) followed by the blunt force of the phrase “we’re not”—all these turns ratchet up the surprise and tension. This is Dickman at his finest. Here is the resilience of a child-speaker, and a rebellious drive against death. Here is an advocate for beauty, a witness to tragedy. When he walks that fine line, when he maintains his balance without falling, it is as good as anything I’ve read in the past few years.

That’s the way to do it

put your face in the dirt

and belt it out(“Imaginary Playground”)

The speaker can be gentle but does not go gently into that good night.

However, when Dickman gets careless, the reader suffers. Dickman eschews punctuation (with the exception of a handful of question marks and exclamation points), forcing/focusing attention on the music of the line. This technique requires a mastery of prosody and unfortunately, I don’t think Dickman is quite there yet. Where white space should reverberate with layered meanings, often time we get throwaway echoes. Where line breaks should lead the reader into delight (or despair as this book may elicit), it often confuses or irritates. Not many writers could (nor would they) end a six line stanza with the single word “and,” yet Dickman does so. Why? I could pull an explanation out of MFA (My Fat Ass), but why over-intellectualize something that does not strike a chord with me? Often times it comes down to either we forgive some moves (and hence justify it) or we don’t.

Dickman has short lines, extremely long lines, enjambments, etc. Though this can create a sense of unbalance (not exactly the same thing as unease), the stuttering speech I hear in my head sometimes sounds like Captain Kirk. In Dickman’s defense, even the canonized WCW does this to me now and again so hey, he’s in very good company.

Speaking of, William Carlos Williams broke his line to emphasize and distort a sentence (successfully creating echoes that were also somehow not echoes); Dickman’s line breaks often seem arbitrary. Sometimes he makes it work. For example, in “Dead Brother Superhero” we have a speaker watching his bedroom door. He counts his breaths “like small white sheep” and ends with this three line stanza:

Any second now

Any second

now

Here is an echo that is not an echo. Dickman plays with time using well-placed breaks in the line. The single word “now” is part command, part instance of time. It has been given new life in the retelling (though it is rather simple). Of course, the speaker isn’t always so clever.

And I am glad

I am glad

I am

so glad(“From the Lives of My Friends”)

These lines could have done so much more work, but instead rehash territory Dickman has already covered (ie: the shorthand I mentioned) with very little pizzazz.

You’re a dog

You’re a fucking

dog

(“Be More Beautiful”)

Again with the predictable line breaks, again with the boring use of a curse word.

Ultimately, we have a very talented writer, a well-read and intelligent writer, who has found early success. He is a very exciting, promising poet who I fear is at risk of becoming a parody of himself (or of the many influences we find in his work). Surreal doesn’t have to mean absurd, but there are several red flags in this book where surrealism becomes an excuse for mediocrity. Flies maintains an interesting tone from the perspective of a young adult (if poetry were more commercially successful, we would file this under “Young Adult Poetry”), but again I find evidence of immature writing hiding behind the guise of an adolescent speaker.

My hope is either Michael Dickman continues to evolve and grow as a writer (thus solidifying and maturing his vision/voice) and/or that editors will work as hard trying to sell Dickman’s poetry as they do Dickman himself (notice how the main attraction of the cover is not the title of the book – which nearly blends into the white space – so much as the author’s name? The title may as well be Michael Dickman Flies.)