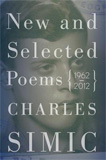

December 30, 2013NEW AND SELECTED POEMS: 1962-2012

Review by Howard Rosenberg

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

215 Park Avenue South

New York, NY 10003

ISBN 978-0-547-92828-9

2013

384 pp., $30.00

www.hmhco.com

In an interview published in The Paris Review, Charles Simic said, “I love odd words, strange images, startling metaphors, and rich diction, so I’m like a monk in a whorehouse, gnawing on a chunk of dry bread while watching the ladies drink champagne and parade in their lacy undergarments.” That love displays itself in the poems in his new book, New and Selected Poems: 1962-2012, most of it culled from thirteen of his earlier works.

Almost hidden near his latest book’s end are the new poems. Many didn’t captivate me as much as ones in his previous works, such as Master of Disguises’ “Summer Storm”: Its style reminds me of Linda Pastan’s, one of my favorite poets. For me, poems need to tell a story that I can invent from, expand upon. In “Summer Storm,” its final quintain both ended the poem and initiated my imagination’s journey. The “deepening quiet” that enters the poem surrounded me as my eyes lingered on its lines. Of the sixteen new ones, six are discussed below, beginning with “I’m Charles” and ending with “In the Egyptian Wing of the Museum.”

“I’m Charles” is the first-person, one-stanza account of its narrator

Swaying handcuffed

On an invisible scaffold,

Hung by the unsayable

Little something

Night and day take turns

Paring down further.

Battling writer’s block, the narrator struggles to express the “unsayable,” warring with a deadline that’s effecting his “last-minute contortions,” the poem animating the difficulty of expressing what’s just beyond the mind’s reach. Rather than relating to the experience literally, Simic mutates it, transfiguring it into a scene whose similes, metaphors, and personifications could have captured Poe’s attention. However, what I enjoyed most was the poem’s abstraction, first a distraction and then an attraction.

“Things Need Me” further displays Simic’s skill at animating the inanimate. Its opening lines, “City of poorly loved chairs, bedroom slippers, frying pans,/ I’m rushing back to you” introduce another narrator—totally different persona, one cognizant of the outer, literal world but not trapped within an internal conflict. The narrator verbally glares at the “heartless people who can’t wait/ To go to the beach tomorrow morning,” people eager to desert the city with its “Dead alarm clock, empty birdcage, piano I’ll never play,” objects the narrator prefers as his companions, “Each one with a story to tell.”

The interaction with the outer world continues in “Lingering Ghosts.” Its narrator asserts, “Give me a long dark night and no sleep,/ And I’ll visit every place I have ever lived,” those lines reflecting Simic’s statement in Dime-Store Alchemy: The Art of Joseph Cornell that “Insomnia is an all-night travel agency with posters advertising faraway places.” When told in an interview published on Terrain.org that “many of your poems seem to take place late at night,” he replied, “As for late-night settings in my poems, it’s my lifelong insomnia speaking. I’m usually up when everyone else is snoring away.” The night seems to guide his vision in ways the day cannot.

In “Ventriloquist Convention,” the narrator addresses anonymous others identified in its opening quatrain:

For those troubled in mind

Afraid to remain alone

With their own thoughts,

Who quiz every sound

The night makes around them …

Then those being addressed are offered an invitation to enter “a room down the hall” where the voices and forms of those not actually there—some deceased— are “All pressing close to you,/ … Leaning into your face,” one person’s “Eyes popping out of his head.” This poem reminds me of those of James Tate, the style change adding spice to Simic’s new poems, its title a lure, its bait worthy of a bite. It’s the second new poem I dwelled upon, treated as a puzzle whose pieces contained a secret I wanted to share.

“Grandpa’s Spells” is another new poem in which the narrator prefers his own company.

Bleak skies, short days,

And long nights please me best.

I like to cloister myself

Watching my thoughts roamLike a homeless family

Holding on to their children

And their few possessions

Seeking shelter for the night.

But the narrator’s favorite thought is of “The dark sneaking up on me,/ To blow out the match in my hand.” The dark’s actions are both a personification and a metaphor for death—a frequent guest in Simic’s poems—as the narrator awaits without fear his dispossession from everything tangible.

Life and death also coexist “In the Egyptian Wing of the Museum.” A man and woman engage in coitus against a coffin painted with death’s rituals

While the dog-headed god

Weighed a dead man’s heart

Against a single feather,

And the ibis-headed one

Made ready to record the outcome.

Preceding the above, final stanza is a middle quintain laden with prepositional phrases—“like an unicyclist,” “up a pyramid,” “in the hands of a magician,” “at a mortician’s convention”—that slow its pace, control its rhythm, and detail the live couple’s unification. Simic’s minimalistic style both sharpens and condenses the reader’s focus and reflects the bond between life and death, creating a verbal representation of the Yin-Yang symbol.

When the new poems’ pull on my attention waned, I returned to earlier times, to poems such as “St. Thomas Aquinas” (in The Book of Gods and Devils), to its six-line stanza that begins with “I stayed in the movies all day long./ A woman on the screen walked through a bombed city/ Again and again” and ends with “I expected to find wartime Europe at the exit.” For a moment, I was more than a reader. I was an observer, the woman walking away from me, the war outside my door.

Also in The Book of Gods and Devils is “The Little Pins of Memory,” a first-person tale recounting a remembered event, one involving a “child’s birthday suit,” “a tailor’s dummy,” and a store that “looked closed for years.” Though the tale’s revealed to be real, to stimulate my imagination I blurred its border between the real and the surreal, an action that many of Simic’s poems easily allow if not already doing that for the reader.

Another of my favorites is “Listen” (in That Little Something). An apostrophe poem, it begins with

Everything about you,

My life, is both

Make-believe and real.We are a couple

Working the night shift

In a bomb factory.

The narrator gives his life a joint existence, treating it as if it’s separate, yet inseparable, one partner a “he,” the other, a “she.” This poem displays Simic’s strength, his ability to mesh seamlessly the real and unreal, using simple language to express complex ideas.

Another earlier poem, “The Common Insects of North America” (in Jackstraws), contains an allure that I wish more of the new poems had. Insects, its narrator proclaims, are all about, “Behind Joe’s Garage, in tall weeds,/ By the snake handler’s church,” among them, “Painted Beauty,” “Clouded Wood Nymph,” and “Chinese Mantid,” all animated by personification. One insect’s “barefoot and wears shades”; another’s “climbed a leaf to pray.” Further, in Simic’s “scene” the insects are not intruders but more like acquaintances who are asking us, through him, to “Please let us be neighbors” a la Mister Rogers.

New and Selected Poems: 1962-2012 offers an excellent selection of Charles Simic’s poetry; however, I wish it included one omission: information about the “nearly three dozen revisions” to previously published poems that its front flap states the book contains.