January 5, 2014PANIC ON THE STREETS OF POETRY

When people ask me how (or why) I became a poet, I always blame music. At 14, I was skinny, unpopular, and shy. My daily life at school was a terror—constant bullying, threats to kick my ass, I’d walk around the campus avoiding eye contact with anyone. My home life wasn’t much better. My mother berated me for being different. The few friends I had were outcasts, and I was lucky to find them. Already an atheist, I had no god to explain the world to me or make me feel at ease. All I had were the lyrics of my favorite singers, and from one band in particular, called The Smiths.

Did I seek The Smiths or did The Smiths seek me? In all truth, the first time I heard them, I can’t say I was impressed. They bored me. Was it an accident that I even became a fan of theirs? Was I just trying to fit in with the few friends that I had? And if so, isn’t it ironic that my willingness to conform is what ultimately led to the discovery of who I am?

I know a lot of people hated them. Or him, I should say—not so much the band, as that whimsical, eccentric, lead singer, Morrissey, who allowed his fans to rip off his shirt and would stroll around on stage with half the local nursery in his back pocket. The same vegetarian freak who would wear a hearing aid though he wasn’t hard of hearing—maybe just a little tone deaf. And, of course, there were the thousands of annoying fans who idolized him.

I know a lot of people hated them. Or him, I should say—not so much the band, as that whimsical, eccentric, lead singer, Morrissey, who allowed his fans to rip off his shirt and would stroll around on stage with half the local nursery in his back pocket. The same vegetarian freak who would wear a hearing aid though he wasn’t hard of hearing—maybe just a little tone deaf. And, of course, there were the thousands of annoying fans who idolized him.

I was one of them.

But whether you hated him or loved him, who could deny he had something to say—even when it was complaining about the fact that nobody else did. Consider these lyrics to the hit single, “Panic”:

Because the music that they constantly play

It says nothing to me about my life

Was this just vanity? Did he literally mean the particular circumstances of his own life? Of course he did and of course he didn’t. He meant nothing less than the shared suffering, love, alienation, drama, and spirit of all our lives. He was trying to say something honest in a decade saturated with the worst of fabrications (hair bands, the lip-syncing Milli Vanilli, the virgin-by-simile, Madonna), which made him a true outcast and a true poet. He was awkward, bookish, shy, and celibate. Morrissey wasn’t just like a virgin, he was one. And the Smiths were a welcome reprise in a decade of sell-outs. They refused to make videos (though they eventually reneged on this promise), refused to ever sell their songs to television, and to this day remain one of the few bands that refuse to get back together for a paycheck (despite the rumors). Not to mention becoming the progeny for so many musical acts that followed, from Radiohead to Jeff Buckley, who came with the talent, if not the literary bravado. But who can fault them for it? Only a handful of lyricists ever really had literary talent and Morrissey is (or was depending what you think of his solo efforts) one of them. Consider this line from another hit “Stop Me If You Think You’ve Heard This One Before”:

And the pain was enough

to make a shy bald Buddhist

reflect and plan a mass murder

Not only is there humor and wit, but you get that it’s a shitload of pain. It’s also not so obscure that you don’t understand it, and he doesn’t dumb it down but assumes you’re smart enough to understand the irony. It’s also not sentimental and cheesy. The thing about Morrissey is that he doesn’t seem to be singing about his pain, he seems to be singing about yours. What he taps into is the secret of all good writing—honesty. Something that so many aspiring and accomplished writers seem to fail at, and, as a result, fail to connect to their potential reader. Unlike for the singer, there isn’t a melody to pick up the slack when the words ring false. In music, the emotional connection may not always depend on the words, but in writing it always does. The work must be done on the page. And if the work is done right, it shouldn’t matter. But how does one do it? Well, this is, perhaps, the mystery of it all. But part of what needs to be there is the desire to connect to others. Despite what people think, Morrissey isn’t actually narcissistic, not when he creates his art anyway, or we’d never be talking about him today (okay, maybe some of us would). He understands that it’s the reader (or listener) who’s ultimately more self-absorbed than he is. After all, they’re the ones looking for a message. Morrissey may ham it up onstage, but when he sits down to write, he transcends all this by allowing a vulnerability to emerge, which, in turn, establishes a deep intimacy with whoever’s listening.

You see a similar honesty, vulnerability, and intimate connection to the audience in a poet like Charles Bukowski. And it’s no mystery why both writers have such a dedicated fan base. Though these two names are rarely mentioned in the same space, both have more in common than we might initially think, not only in their honesty and ability to connect intimately with their readers/listeners, but in their status as outsiders. It’s not always clear with Morrissey (as with Bukowski) how much is persona and how much is person (strangely, Morrissey’s personal life is very secret). But whatever facts may be skewed, the emotional and psychological truths of rejection, loveless-ness, loneliness, alienation prevail in both of their works.

Consider the lyrics to a song like “Hand in Glove.” There have been different interpretations of this song, from a depiction of closeted homosexuality to two adolescents who want to believe their love is unique in the history of the world, to an autobiographical account of the relationship between Morrissey and Smiths’s guitarist Johnny Marr. Whatever interpretation, the song is a depiction of two outcasts who have found each other, who have “something they’ll never have.” In other words, the “they” who feel comfortable in their own skin, who are content with their lives or loves, who fit in. Two outcasts finding each other is a momentary and hopeful reprieve in a world of isolation, before it all breaks down again—or at least the narrator projects this, recognizing outcasts generally stay outcasts, that loneliness and rejection persist, that all human connection, outside of art, is only temporary:

But I know my luck too well

yes, I know my luck too well

and I’ll probably never see you again

I’ll probably never see you again

A different kind of alienation is depicted in a song like “Barbarism Begins at Home” which demonstrates society’s attempt to force conformity on the outsider beginning, as the title suggests, at home:

A crack on the head

is what you get for not asking

and a crack on the head

is what you get for asking

But with Morrissey’s honesty also comes great humor. Laughter, of course, is another way to connect to others. This is something few seem to understand about his lyrics—they’re also, at times, very funny. Take for instance, these well-known lines from “Heaven Knows I’m Miserable Now”:

I was looking for a job and then I found a job

And Heaven knows I’m miserable now

Or these from “Sweet and Tender Hooligan:”

Poor old man

he had an “accident” with a three bar fire

but that’s OK

because he wasn’t very happy anyway

Poor old woman

strangled in her very own bed as she read

but that’s OK

because she was old and she would have died anyway

This shouldn’t be funny, but it is. At the same time, in a song that is purported to be about someone in love with a murderer and how love can blind us, Morrissey manages to humorously and seriously convey the sad lonely desperation of both lover and victim and murderer. Only to top it off with a cheeky (in this context) quote from the Book of Common Prayer:

In the midst of life we are in death, Etc.

No writer I know of has ever made such a profound and hilarious use of “Etc.” Yet, again, when he sings it, it’s like he’s sending a message directly to you: death is a part of life, he says, but stops short of becoming too polemical or preachy, when he adds that last apathetic touch of Etc., or yeah, yeah, yeah, but you’ve heard it all before. And just to make sure, he takes it one more step by punning the line at the end of the song, by changing “death” to “debt.”

The point is not that you should run out and buy (or rather, download) every Smiths album or even like the band. Many don’t and never will and need not. Many also have no use for music or lyrics or poetry at all. We don’t need to worry about them. They’re hopeless and more than likely, richer than us. But many people, whether we admit it or not, turn to art for guidance just like some of us might turn to, ahem, religion. It’s a lie that we find who we are by simply looking “inside” ourselves. This sort of navel-gazing, for the most part, only produces bad poets and psychopaths. Good art serves a different role, like all great mythology, which is to tell us something about our lives. This is the function of all the greatest myths, all the greatest stories, all the greatest song lyrics, and all the greatest poetry.

Flash forward almost a quarter century:

I’m 39, not-so skinny, still unpopular, and still shy. My daily life at school is still a terror, but now I’m the teacher. The constant bullying hasn’t stopped, but rather than it be by football players, it’s by administrators and politicians. The threats, however, to kick my ass have died down. That being said, I still walk around the campus avoiding eye contact with anyone. At home, it’s a little better. My mom has been replaced by my wife, and she only occasionally berates me for being different. The few friends I have are still all outcasts, and I still feel lucky to have them. I’m still an atheist, still without a god to explain the world to me (though I do have science), and for the most part my favorite singers have now been replaced by my favorite writers.

I’m 39, not-so skinny, still unpopular, and still shy. My daily life at school is still a terror, but now I’m the teacher. The constant bullying hasn’t stopped, but rather than it be by football players, it’s by administrators and politicians. The threats, however, to kick my ass have died down. That being said, I still walk around the campus avoiding eye contact with anyone. At home, it’s a little better. My mom has been replaced by my wife, and she only occasionally berates me for being different. The few friends I have are still all outcasts, and I still feel lucky to have them. I’m still an atheist, still without a god to explain the world to me (though I do have science), and for the most part my favorite singers have now been replaced by my favorite writers.

Just last month, I attended a number of poetry readings. One stands out more than the others, but not for the reasons you might think. It was at the university where I work. The poet gave some staggering statistics, claiming that in 1950, there were only 100 or so poets publishing in the English language, and today there are over 20,000. This left me wondering, with so many poets out there, why is it so hard to find one that tells me something about my life? Of course, it only took a few minutes to answer the question when this esteemed, award-winning poet delivered his poems. As one of my colleagues would later say, “It was like he ripped down the middle of the newspaper and just read it to us.” I suddenly felt excluded from an elite (or elitist) club. For the next twenty minutes I sat there listening to him wishing I had been closer to the exit. The poet made it a point to tell us one of the poems he read was part of a longer poem he’d been working on since 1975 or something like that. All those years and not one goddamned thing to tell me about my life. In his defense, he gave the disclaimer that only he could understand some of the references because they were personal. Which left me wondering, how much was the college paying this guy? And what were all these young people in the audience supposed to get out of this?

Did The Smiths lead me to become a poet or did the poet in me lead me to like The Smiths? None of my friends who introduced me to them ended up writing poetry. Thanks to Facebook, I now know that the guy who first introduced me to The Smiths is a lawyer (probably the wiser “career” choice.) Another big Smiths fan I know works in advertising. And still another I met much later in life, runs self-help seminars—go figure. Others expectedly became musicians as I did for a time in my life, before I concluded that it was a misguided venture for me—though I loved music, what I loved even more were words. I just hadn’t needed them yet.

What the lyrics of The Smiths did, more than anything else, was inspire me at a time when I needed it most, in ways that much of contemporary poetry is failing to do (or unwilling to do) for young people today. And it wasn’t just the lyrics, it was the word culture they introduced to me. For the first time in my life, I became interested in writers. After all, what other rock band mentioned Keats or Yeats or Oscar Wilde or all three in one stanza, as what happens in “Cemetery Gates:”

A dreaded sunny day

so I’ll meet you at the cemetery gates

Keats and Yeats are on your side

while Wilde is on mine

What other band even thought of putting someone like Oscar Wilde on their t-shirt? Or as a backdrop to their stage show? Who else would title one of their songs “Shakespeare’s Sister”? What band in the history of rock and roll made young men and women excited to attend their English class? I remember going to the public library with my mom and picking out an 800-page biography of Wilde when I was fifteen years old solely because of The Smiths. And even if I couldn’t get through it all, I knew there was something magical and important about it. I knew or hoped, anyway, that within literature lay the answers to all my growing pains as I transitioned into the adult world. My sophomore book report was on The Picture of Dorian Gray, which I loved, and which was a book I’m almost certain my high school English teacher didn’t know (strangely, but that’s another subject.) I wouldn’t have known it either had it not been for The Smiths, and Morrissey in particular, who made it okay, even cool to be smart and read literature, in a way that no one else from my generation had.

There were, of course, all those poets and novelists that came later: Charles Baudelaire, Bukowski, Ernest Hemingway, Fyodor Dostoevsky, Carson McCullers, Fernando Pessoa, Herman Melville (see Morrissey’s solo song “Billy Budd”). But, to me, The Smiths were an unlikely entry-point into what would become the greatest passion of my life. Maybe it was because Morrissey was more poet than pop star. Or maybe it was generational. After all, there had been other poet/pop stars, of course—Leonard Cohen, Bob Dylan, Jim Morrison, Patti Smith. But Morrissey was more freakish than they were. You got the impression they would be the life of the party while he would be standing in the corner. By the time I was born, they already belonged to the club. And though they all had something to say, he was singing to a different crowd—those who were too shy to leave their bedrooms, those who were bullied, those who felt rejected, those who were outcasts. He was singing to me.

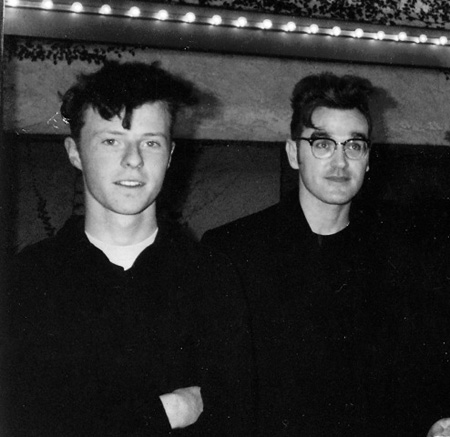

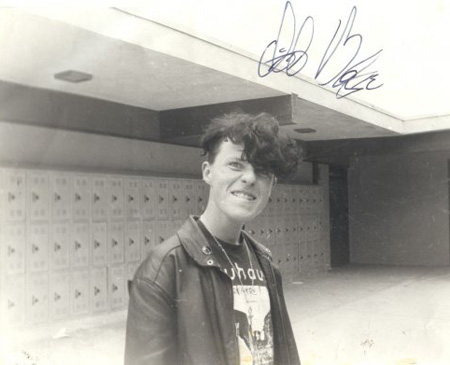

Photos (courtesy of author): Clint Margrave with Morrissey in front of his hotel (Le Parc in Hollywood) circa 1990; Clint Margrave in high school.