May 1, 2015Pixel Poetry: A Meritocracy

The Only Things Worse Than Generals Are Generalities.

In serving the online literary community as critic, columnist, moderator, administrator, contest facilitator, technician, consultant, designer, and programmer for the last quarter century, I’ve been struck by the differences between its communities and products and those of the offline or “real” world.

When internauts speak of “online” poetry they really mean “online workshoppers’” poetry, not what is found on blogs, vanity sites and personal webzines. For example, the loveable, irrepressible Bill Knott may be the Walt Whitman of our time, promoting, selling and giving away his work. Because he does much of this on the internet, offliners might consider him an online poet. No one who has been plugged in for more than a decade would agree. Similarly, every word that Shakespeare ever wrote can be found on various sites but he’s hardly an “internet poet.” Magazines archiving older issues online don’t make for “online poetry” in any but the most literal sense. Conversely, if Usenet star poet Robert J. Maughan scratched some verse onto birch bark 200 miles from the nearest computer and published it in The New Yorker it would still be an online poem. What distinguishes pixel from page poetry isn’t where it is written, revised, reviewed or published, but whether or not the poet’s technical and critical skills reflect time spent in an online workshop.

At the risk of oversimplification, page poetry is about poets, pixel poetry is about poems. To an offliner, a poem may be a poet’s greeting or business card, a piece in a self-portrait jigsaw puzzle or an invitation to psychoanalysis. “Pragmatic” and “professional” describe what we find in poetry books and magazines. The careerist track of aspiring academics is the most salient example. In this publish-or-perish environment, people more interested in and better suited to teaching poetry than writing it are driven to use up print publishing resources. This impetus, along with other commercial motivations, is unique to the print world. One obvious ramification is that the once common practice of publishing poems anonymously or pseudonymously is unthinkable to today’s print poets.

In contrast, the pixel poet is both a “purist” and an “amateur” who, for better or worse, views each poem as a isolated specimen. Unless part of a series, each poem will serve as its own context. As for the author’s role in this exploratory surgery, well, the biologist rarely speculates about the Creator. Think New Criticism, minus the crazy parts.

When offliners think of workshops they imagine face-to-face (F2F) settings, either writers groups or MFA-style peer gatherings. Academic workshoppers tend to share similarities including occupation (student?), esthetic, education, locale and age. In either model the circumstances can make objectivity and candor difficult. Critics need distance, including physical space. The same verse submitted to an online critical forum may be examined by readers from all continents, ages, occupations, styles and knowledge levels. If posted to an expert venue, a poem might attract the attention of some of the greatest critiquers alive: Peter John Ross, James Wilks, Rachel Lindley, Stephen Bunch, the Roberts (Schechter, Mackenzie and Evans), Richard Epstein, Hannah Craig or John Boddie, to name only a few. There is, quite literally, a world of difference between F2F and online workshops. This diversity and sophistication avoids the homogeneity that F2F workshops can spawn. It also explains why the word “peer” is less frequently used to describe online workshops.

What traits do online workshoppers have in common? The pixel poet must have an abiding interest in improving, obviously, but also in the elements, rather than just the products, of the craft. This is not the place for those who neither know nor care to know that “Prufrock” is metrical. This is not the place for “substance over form” advocates blurbing profound prose with linebreaks. This is not the place for, as Leonard Cohen would say, “other forms of boredom advertised as poetry.” This is a meritocracy of poems, and no one is better than their current effort. If Shakespeare himself posted a clunker to one of the expert-only venues he might be confronted with comments like:

“You use words like a magpie uses wedding rings.”

—Gerard Ian Lewis

“Please tell me there were no dice involved in choosing your words.”

—Manny Delsanto

As you can imagine, the online workshop breeds humility and respect for the art form.

The rules are simple: Critique as much and as thoroughly as you can and thank those who grace you with their thoughts. Newcomers to internet workshopping are urged to start on one of the “friendlies.” Of these, let me recommend:

In general, the poetry and critique on these venues is about what you’d expect from novice forums but one can, at the very least, use this introductory period to read guidelines and develop the mechanics of threading, posting and creating links and attributes. Through many of these sites aspiring acolytes can participate in the InterBoard Poetry Contest (IPBC).

Serious students are encouraged to lurk and learn on the expert venues for a few months until they are ready to participate:

Both of the latter accept novice members but PFFA’s idea of a “novice” translates to what offliners would consider “experienced.” PFFA and Poets.org also host two of the three best online learning resources:

Glossary of Poetic Terms from Bob’s Byway

A Brief History of Time Online

Thus, the pixel poetry milieu is, in fact, two supercommunities: serious and friendly. These can usually be differentiated by the presence or absence of active technical and theoretical fora. Both metagroups produce their share of prominent figures and lasting relationships. Both site types welcome “board-hoppers”; many people are members of all four serious venues.

The first difference that might strike newcomers to e-poetry is the gender balance. From workshoppers to webzine editors and contributors, women are better represented in cyberspace than in print. Online, males significantly outnumber females only in the blogosphere, a milieu that most webziners and pixel poets assiduously avoid.

Content Is Cargo, Verse Is Vessel.

Pixel and page criticism and poetry occupy opposite ends of the form-versus-substance teeter-totter. No matter how profound the prose, onliners are far less likely to accept it as poetry. Interpretation, which is central to academic criticism, is the least significant aspect of serious online workshop critique.

Almost nothing is known about the author of our first example. D.P. Kristalo posted primarily to Poets.org and Gazebo in 2007. Even DPK’s gender is unknown, but in discussing the poet most use feminine pronouns. Because the internet serves as an outlet for those in need of anonymity, onliners consider it bad form to speculate about identities. As we’ll see, many of the best internet poets are frustratingly shy about their work. To my knowledge, not one of the poems reprinted here was ever submitted over the transom.

Good Actors Pause for Breath. Great Actors Pause for Thought.

“Beans” (Fig. 1, click to enlarge) is the archetypical online poem: superbly crafted, original and fascinating from a technical, intellectual and emotional perspective. The fact that it is a curgina (i.e. verse with free verse linebreaks, like the bacchic monometer of “We Real Cool” by Gwendolyn Brooks) reflects the higher mix of metered work found online. Its tautness reflects the online workshop’s discipline. The unusual subject matter and treatment reflects the pixel poet’s reader-orientation. A teacher could spend days describing the merits of this acrostic: the terminal diaresis in stanza 1, the “aw” and “l” sounds slowing down the read for the denouement, the triple entendre of “coppers,” the dramatic ambivalence and ambiguity of “Valparaiso” (birthplace of both the coup and its principle victim), the cautious euphemisms that begin most of the lines (and explain the erratic linebreaks), etc.

“Beans” (Fig. 1, click to enlarge) is the archetypical online poem: superbly crafted, original and fascinating from a technical, intellectual and emotional perspective. The fact that it is a curgina (i.e. verse with free verse linebreaks, like the bacchic monometer of “We Real Cool” by Gwendolyn Brooks) reflects the higher mix of metered work found online. Its tautness reflects the online workshop’s discipline. The unusual subject matter and treatment reflects the pixel poet’s reader-orientation. A teacher could spend days describing the merits of this acrostic: the terminal diaresis in stanza 1, the “aw” and “l” sounds slowing down the read for the denouement, the triple entendre of “coppers,” the dramatic ambivalence and ambiguity of “Valparaiso” (birthplace of both the coup and its principle victim), the cautious euphemisms that begin most of the lines (and explain the erratic linebreaks), etc.

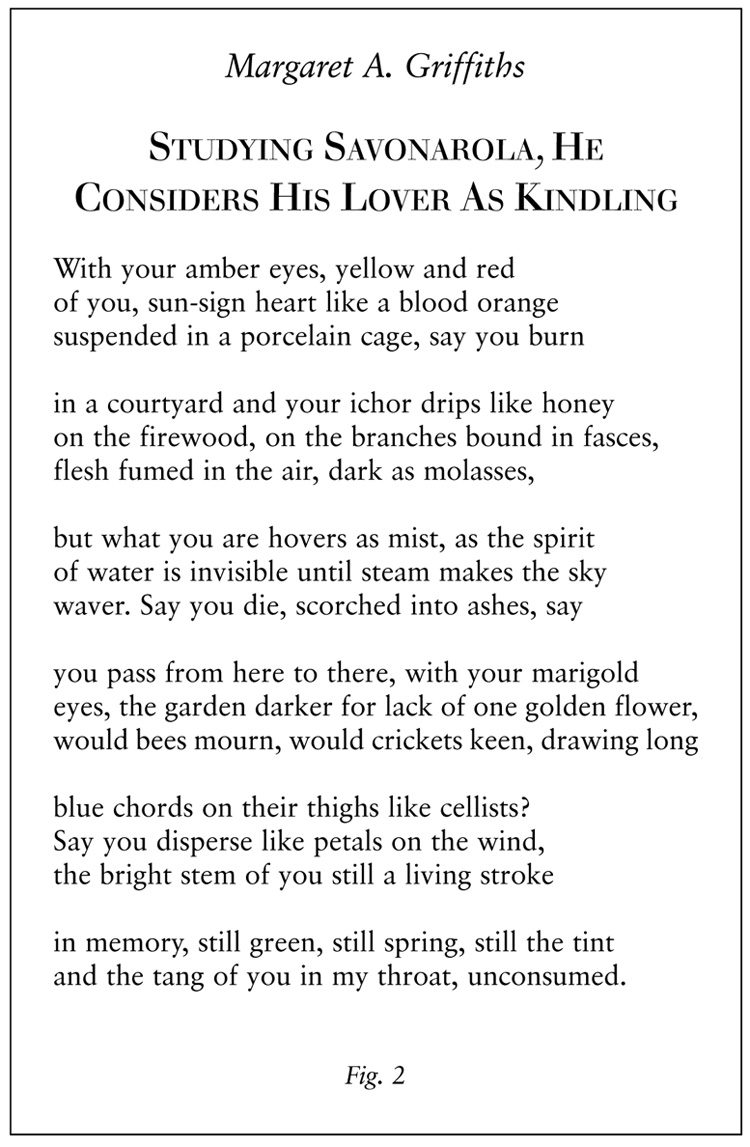

Ask who the best contemporary print poet is and you’re bound to get a wide variety of responses: Walcott, Heaney, Laux, Hill, Cohen, etc. Ask about the best online poet and you’ll get one answer: the late Margaret A. Griffiths, aka “Maz” or “Grasshopper.” In a 2005 poll, members of the expert community declared Maz the poet they’d most want to see in an anthology. This was five months before her signature masterpiece (Fig. 2) was written and five years before it was published (posthumously).

When Margaret died suddenly in 2008, a throng of admirers worldwide began scouring archives and hard drives, collecting hundreds of her poems. These were recently released by Arrowhead Press in a volume called Grasshopper: The Poetry of M A Griffiths. This book is a must-own for any serious student of the craft.

When Margaret died suddenly in 2008, a throng of admirers worldwide began scouring archives and hard drives, collecting hundreds of her poems. These were recently released by Arrowhead Press in a volume called Grasshopper: The Poetry of M A Griffiths. This book is a must-own for any serious student of the craft.

Of course, most pixel poets aren’t as introverted as Maz and DPK. Nevertheless, the point is made that as a group, unlike Bill Knott, pixel poets are not great self-promoters.

Online poetry has a longer history than many imagine. For fifteen years before the web arrived in the mid-1990s the only game in town was the rec.arts.poems newsgroup on Usenet (and its echo chamber, alt.arts.poetry.comments). This was the greatest single meeting of poetry authorities in history. Nevertheless, it was a relatively unknown contributor, Marco Morales, who wrote this classic “killer and filler” poem:

Hookers

Missing you again,

I embrace shallow graves.

Pale faces, doughlike breasts

help me forget.

The poem is about “me missing you” and, sure enough, those are the only words that have vowel sounds absent from that killer second line. Don’t let the L1 acephaly or L4 trochaic inversion fool you; “Hookers” is blank verse: iambic trimeter, ending in a dimeter. The “three tris per dime” ratio gives the form its name: a carnivalia.

Usenet was the source not only of the online workshop ethos but of many invaluable truisms as well, including:

Tigger’s Tip #14:

“Every modern poem must contain at least one em dash abuse.”

McNeilley’s 4th Dictum:

“Cut off the last line! This will make your poem better! (If this doesn’t work, keep cutting off the last line.)”

The 1st Law:

“Never say anything in a poem that you wouldn’t say in a bar.”

The 2nd Law:

“If you can’t be profound be vague.”

The 10th Law:

“Don’t emote. Evoke.”

The 12th Law:

“Try to be understood too quickly.”

Egoless Maxim:

“If you don’t think your poetry is competing against the works of others you’re probably right.”

Is pixel poetry superior to what is produced elsewhere? Consider what these poems go through. First, they are written with a critical audience in mind. As we saw with “Savonarola,” a first draft posted to a serious online forum may well be as good as anything found in print. Second, they run a guantlet of some of the planet’s best critics. Knee-jerk revisions are discouraged. Lastly, they are produced by people who have spent more time learning the difference between diaresis and diahrrea than fretting about how many times certain poets cheated on their spouses. Given all of this, shouldn’t we expect them to be better? Not surprisingly, pixel poets have won just about every contest and prize that has blind judging. The Nemerov is practically owned by Eratosphereans. Editors recognize pixel poets’ names and report that their acceptance rates are much higher than those of others.

Where do pixel poets publish? Almost anywhere, but favorite haunts include Rattle, Raintown Review, Measure, The Pedestal, The Dark Horse, The Hudson Review, Lucid Rhythms, thehypertexts.com, 14 by 14, Shit Creek Review, The Flea, and Autumn Sky Poetry. In short, pixel poets tend to seek editors whose understanding of the craft and technology matches their own.

There is a subtle difference between many webzine editors and their print counterparts: The latter want first; the former want best. To wit, if we look at the major literary print concerns, every single one demands first publication rights. As you may know, Poetry magazine was neither the first nor the second to publish “Prufrock.” Thus, T.S. Eliot’s masterpiece couldn’t be submitted to a print venue today. Needless to say, most webziners would do cartwheels before republishing it.

The lack of financial motivation creates an interesting paradox: With no sellers or market it becomes a sellers’ market. Let’s look at this from an editor-in-chief’s point of view. Remember that cartoon where one vulture turns to another and says: “To hell with this waiting. I’m gonna go kill something!” Many proactive editors are establishing a personal presence in online critical fora. Want to publish a book that may cover your costs in pre-orders? Consider one of the higher profile pixel poets. Seeking a stunning poem to headline your ‘zine? Ask one of the regular online workshop critics for a recommendation.

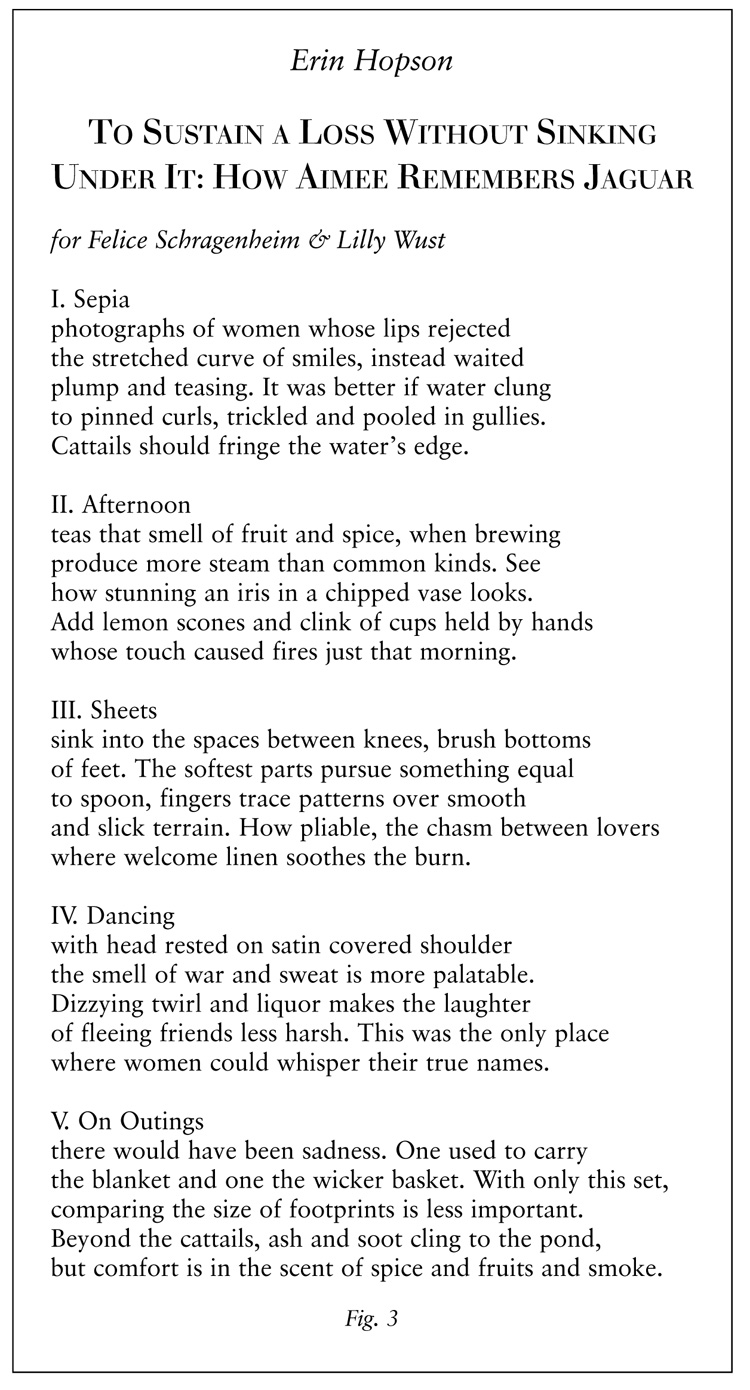

Now let’s view the poems-not-poets, best-not-first emphasis from a pixel poet’s perspective. In 2006 a young, unknown writer, Erin Hopson, posted a poem to Gazebo. Normally reserved critics raved about it, one gushing: “This is award-winning writing. Change nothing.” Four years later, during which time the author completed a college degree, the poem still languished in the author’s drawer. Critics have long memories, though. And hard drives. In 2010, during a conversation with thehypertext.com editor Mike Burch, that critic presented a copy of that poem for consideration. Not surprisingly, Mr. Burch freaked. One womanhunt later, the poet, who thought it a prank at first, was contacted. In short order this sensuous ekphrasic brilliancy, based on the Max Färberböck 1999 film, Aimee and Jaguar, was published. (Fig. 3)

Now let’s view the poems-not-poets, best-not-first emphasis from a pixel poet’s perspective. In 2006 a young, unknown writer, Erin Hopson, posted a poem to Gazebo. Normally reserved critics raved about it, one gushing: “This is award-winning writing. Change nothing.” Four years later, during which time the author completed a college degree, the poem still languished in the author’s drawer. Critics have long memories, though. And hard drives. In 2010, during a conversation with thehypertext.com editor Mike Burch, that critic presented a copy of that poem for consideration. Not surprisingly, Mr. Burch freaked. One womanhunt later, the poet, who thought it a prank at first, was contacted. In short order this sensuous ekphrasic brilliancy, based on the Max Färberböck 1999 film, Aimee and Jaguar, was published. (Fig. 3)

Candid, informed criticism isn’t for everyone. The vast majority of poets are unfamiliar with Scavella’s mantra (i.e. “I’m not as good as I think I am.”) and have no interest in improving their work through such scrutiny. That, then, is the conundrum:

Critique can boast

when pride has ceased:

who needs it most

will seek it least.