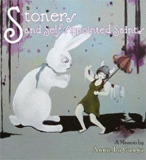

December 20, 2009STONERS AND SELF-APPOINTED SAINTS by Annie La Ganga

Review by Ross Losapio

STONERS AND SELF-APPOINTED SAINTS

by Annie La Ganga

Red Hen Press

P.O. Box 3537

Granada Hills, CA 91394

ISBN 978-1-59709-155-8

2009, 73 pp., $15.95

www.redhenpress.org

I’ve seen it, I’ve seen all this before. I’ve met monsters, hell, I took them camping and out for frozen yogurt on the way home.

(“The Tour Guide’s Apology” )

Annie La Ganga’s memoir, Stoners and Self-Appointed Saints, transports the reader somewhere dangerous, sexy, and smoky. It delivers a payload of drugs, monsters, and self-loathing at a dizzying pace. Reading it is like experiencing the progressing symptoms of an overdose.

At first glance, the work’s integrity as a memoir comes under scrutiny. We see (hear, smell, and even taste) many of La Ganga’s stoner, failed-artist friends, but her own family and personal history are glossed over. For instance, in revealing the circumstances of her mother’s seizing death on the kitchen floor, she devotes an equal amount of page space to describing a responding fireman’s watch:

He said it was for diving in the ocean and telling the time so you could know how many breaths you had left before you had to go up.

(“Three-Minute Memoir” )

Section titles like “Three-Minute Memoir” seem to devalue the author by condensing her life to the length of a pop song. Similarly, “Three Important Stoners” places emphasis on otherwise anonymous friends. As the reader progresses, though, it becomes clear that there is more to learn about La Ganga from the relationships she chooses than from those she inherits.

Hunger is the driving force in La Ganga’s memoir: the desire to devour everything around her and, in doing so, complete her own fractured identity. For instance, she is beside herself with joy after embracing a low-carb diet and eating a pound of ground hamburger. The next day, her mood plummets when the holiday season draws attention to her professionally successful friends and relatives. Later, a contact high from an evening with her pot-smoking neighbors and the prospect of buying a new pair of Nikes convinces her that life is worth living after all. She is the ultimate consumer. Upon seeing her American Express card cut up in a jewelry store in California, La Ganga panics:

There was no distinction between me and my credit. I ruined myself and then had to keep ruining myself even more dramatically to get rid of the shame that made my ears hot and made me crave tacos from Jack in the Box…

(“Money Matters”)

She needs money, but only as the means to another end. Credit becomes marijuana, colored pencils, and fast-food burgers. What money cannot buy, she purchases with her body and soul. She dates whole families at a time. She welcomes iguana owners and self-diagnosed werewolves into her life and then invokes satanic rituals to punish them after the novelty of their presence wears off. When faced with the prospect of actual love for another person, La Ganga recognizes it but decides it is too complicated to be worthwhile. She cannot find love on a drive-thru menu; therefore it does not exist in her life.

[Love] is like a pomegranate, so many pieces to pick out, such a big mess, and you never get full. But what other fruit is so gorgeous and interesting and filled with tiny sparkling jewels?

(“A Waitress in Love” )

La Ganga’s anecdotes draw the reader in, but her writing is strongest when contemplating what it means for her to be a writer and an artist. She slips away from straightforward storytelling and allows metaphor and imagery to rule her description. The result is a headier brew than much of the text, but, ultimately, a more satisfying one. Every role that La Ganga assumes (daughter, drug user, lover, etc.) gives way to that of artist, though she rarely produces proof of it.

I want poems every day and effortless symphonies. I want hot and cold running. I want the sing-song magic voice that makes everything, even cheap toilet paper, feel like a paycheck.

(“Patience is a Virtue” )

If this memoir is about anything, it is about pursuing validation as a person and as a writer. By the end, the reader does not feel any affirmation, but senses its presence in the room like a ghost. Anyone can relate to the struggle to create something meaningful and have it appreciated. La Ganga’s story is not new, but her approach to telling it is..

To that end, Stoners and Self-Appointed Saints represents problem and solution, argument and evidence. The prose poem is a difficult form, but La Ganga executes it better than most throughout her memoir. The narrative’s role in prose poetry is passionately debated and the genre line is constantly toed. Stoners and Self-Appointed Saints sidesteps the argument by focusing each episodic section on a distinct character, emotion, or moment in time. No strict narrative is ever created, but a cohesive memoir is formed by recognizing the impact of these people and events in the author’s life. La Ganga also tempers the form’s somewhat weighty and complex nature by including more traditional poems, lists, and diary entries. The end product races through the reader, almost of its own volition, like a drug entering the blood stream.